The Dutch government says it is helping Mozambique combat poverty and corruption, but the dirt-poor country has extensive gas reserves and these prove more important. Documents obtained by the Freedom of Information Act reveal how closely the Dutch embassy and Shell work together.

“They didn’t tell us a thing,” says an inhabitant of Quitunde, a rural village in the north-western province of Cabo Delgado in Mozambique. “People came, marked the coconut palms with paint and left.”

Quitunde is situated in a region of subsistence farmers, coconut palms and modest homes. In recent years however, they have increasingly been visited by staff from major gas companies such as Shell and Anadarko. Often in a rush, “not even taking the time to sit down,” one of the villagers tells us.

The companies want to build their industry in this gas-rich area and are legally required to negotiate with villagers about their resettlement. There is, however, no healthy dialogue, the locals say. And why have those trees been marked? “We know it is one of the areas other communities will be resettled in, but we don’t know if that’s what this is about.”

This is symptomatic of the current situation in Mozambique where an enormous gas field was discovered in 2011. There can be no doubt that the country will change substantially. But how, and who will benefit from this change remains to be seen.

Another question arises as well: what will the role of donor nations such as the Netherlands be in this transformation? Alda Salomao, a lawyer for the NGO Centro Terra Viva who focuses on land rights is in two minds about it all. “The Netherlands was of great help to this country’s agricultural sector,” says Salomao. However, she is also aware that donor countries such as the Netherlands help ‘their’ gas companies in Mozambique and those companies violate land rights. “Company interests prove to be of paramount importance.”

Independence

For the time being, Mozambique still suffers all the ills of a developing country. It is poverty stricken and underdeveloped; half the country’s 29 million inhabitants live under the poverty line and three quarters of the working population is dependent on agriculture. The government is dependent on international donors for approximately a third of its budget, and this encourages corruption. Mozambique is worryingly far down on the 180-country Transparency International corruption list coming in at 153rd (the lower down, the more corrupt). The country also has a long history of political violence. The Marxist guerrilla movement Frelimo declared independence from its Portuguese colonisers in 1975, but then became entangled in a civil war with the anti-communist Renamo party. Even though the war officially ended in 1992, violence still regularly flares up between the two groups.

However the gas provides hope. The enormous gas field off the coast of the northern province of Cabo Delgado – measuring some 7,000 billion cubic metres (the world’s fourth largest offshore gas project) – the country could transform into a genuine up-and-coming economy comparable to the metamorphosis undergone by oil-rich Qatar. People hope that, many years after gaining political independence from Portugal in 1975, this gas field will provide the required economic independence.

Mutual benefit

In the eyes of the international business community the country has suddenly become one full of economic opportunities despite its political instability, poverty and corruption. The global gas industry has planned 50 billion dollars in investments aimed at extracting the gas. For reference: in 2016 Mozambique’s GNP was only 12 billion dollars.

Dutch companies are also in on the action. Shell (NL) has already acquired a permit, just like other major gas companies including Anadarko (VS), ExxonMobil (VS) and Eni (Italy). Heineken has predicted increased demand for beer in Mozambique and is constructing a brewery there.

Convenient for the Dutch corporate sector was that, immediately after the discovery of the gas field, the Dutch government decided to adopt new development policies in which aid relations increasingly became trade relations. Supporting Dutch businesses in up-and-coming markets is in line with this policy. ‘Aimed at mutual benefit,’according to Minister of Foreign Affairs Frans Timmermans in 2013 (translated from Dutch). ‘Dutch firms aren’t coming here to make a quick buck,’ Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation Lilianne Ploumen assured her audience during a trade mission to Mozambique in 2014.

That may sound good, but it remains to be seen whether that ‘mutual benefit’ also includes the majority of Mozambicans.

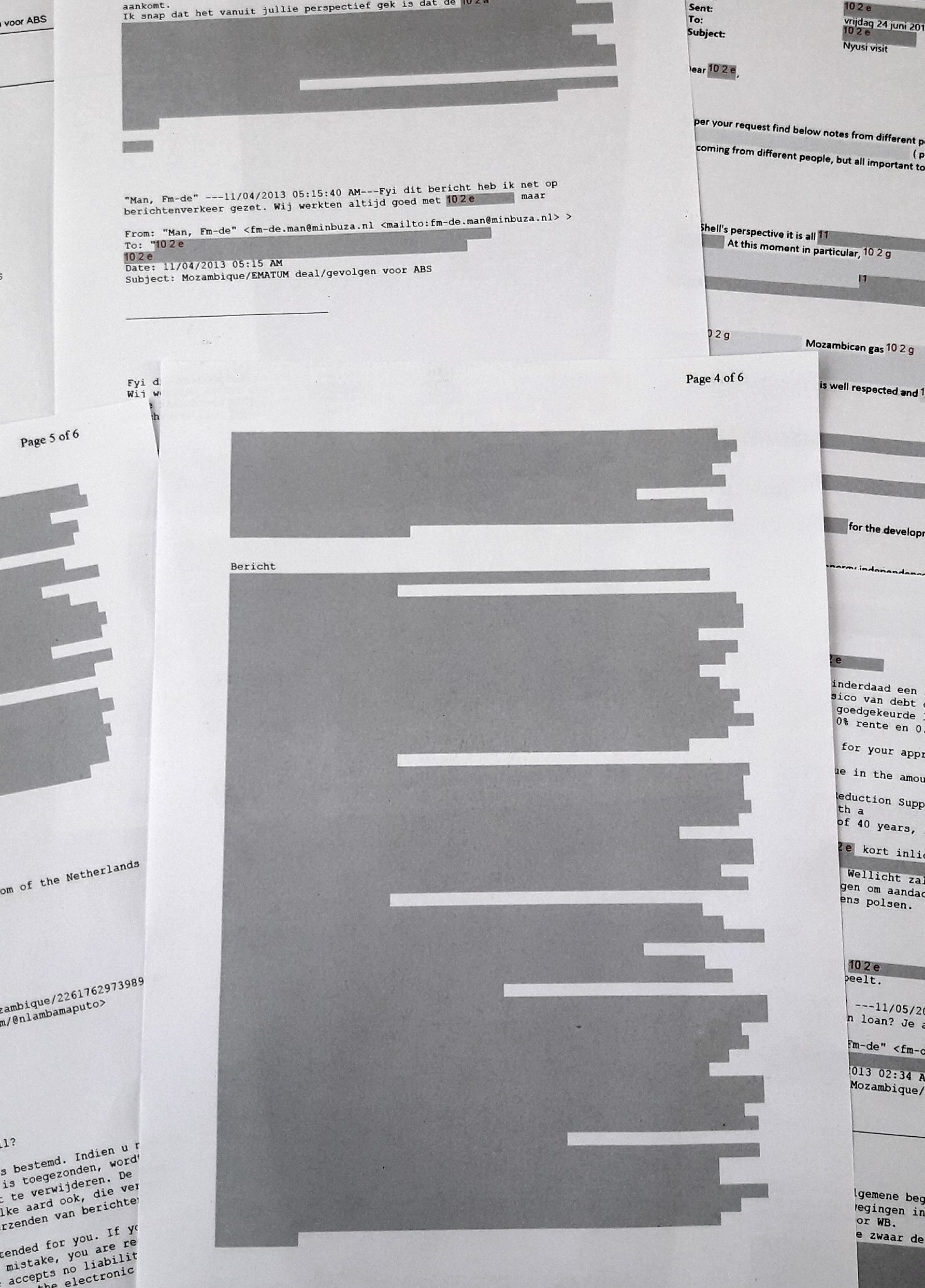

Documents obtained using the Dutch Wet Openbaarheid van Bestuur or freedom of information act reveal a much less rosy picture. A major proportion of the text has been blacked out, concerning which we are still in appeal, see box. The documents reveal a government that has Shell’s gas profits and Heineken’s beer turnover high on the agenda and collaborates closely with Shell to this end. A government which on multiple occasions is losing sight of the interests of the Mozambicans themselves.

First and foremostly that applies to the villagers whose land rights are under threat from companies such as Shell, but it also affects Mozambique in general. The country’s debt crisis was caused by a billion dollar fraud that ran through the Netherlands, a ‘conduit country’ used for tax avoidance. If it is up to the Dutch government another handy fiscal relationship with the Netherlands will be created, benefitting multinational companies.

The Netherlands’ support for Shell in Mozambique is also hard to reconcile with one of the government’s climate objectives (translated from Dutch): ‘increasing access to sustainable fuels in developing countries’. Gas is not sustainable and actively contributes to climate change which, as the government recognises, developing countries ‘will be the first to notice’.

The wob [FOIA] request and the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Finance’s black markers

A freedom of information act (FOIA) request was submitted in July 2017 for this series on Mozambique to the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Finance, Justice and Security, De Nederlandsche Bank [Dutch national bank] and the Public Prosecution Service. Although we received thousands of documents, most in Dutch, a great deal of crucial information was censored. Almost everything concerning the activity of Dutch businesses, the Dutch tax treaty with Mozambique and the Dutch involvement in the Mozambican debt crisis was blacked out.

For example, what did:

• Ambassador Pascalle Grotenhuis discuss with Shell concerning President Nyusi’s visit? (View the censored document here.)

• Shell provide as talking points for the meeting between Prime Minister Mark Rutte and President Nyusi? (View that document here.) And why have parts of this document been refused on the grounds of refusal reason 10.2.a? The latter only applies to government information which the release of might damage relations with international organisations or countries. This emphatically does not cover information from third parties.

• Prime Minister Rutte ultimately say during the meeting? (View that document here.)

• De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) answer to the questions posed by the Ministries of Finance and Foreign Affairs about their investigation into the Dutch trust office TMF? (View that document here.) And why does DNB’s confidentiality agreement apply to journalists, but not to civil servants?

• The Ministry of Finance use as grounds for refusing all request for forms concerning export credit insurance? These forms are to be completed by contractors to ensure that the projects do not have possible negative environmental and social effects. The ministry refused to provide the completed forms. Questions include whether or not the possibility exists that a project might lead to child labour. The ministry refused to release this information on the grounds that it was company sensitive. (The empty and refused request forms can be found here.)

The fact that these and many other questions remained unanswerable was reason for the Platform Authentieke Journalistiek to take the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Finance to court. Because, as we stated in our letter of objection: ‘If companies wish to have company data safeguarded, they should not rely on the public domain. If a company utilises, for example, the financial backing or the facilitating role of the government, then citizens have a right to know’.

However, our appeal procedure is a time consuming matter that could take many more months. We are blogging about the arduous procedure and how taxing this is to a small team of journalists, for Down to Earth magazine.

Shell’s GTL facility

Shell’s gratefulness for the help the company received from the Dutch embassy by promoting Shell in Mozambique is apparent, among other things, from a letter to Ambassador Pascalle Grotenhuis, sent on December 4th, 2015.

‘Your dedication to trade and investment opportunities in Mozambique has been of immeasurable value to our activities and the future of our project’

Shell writes. Grotenhuis forwarded the message to her team from her iPhone.

‘This one is for the whole team! Thanks a lot for all of you!’

The Dutch embassy has been promoting Shell to the Mozambican government for years. This is crucial to Shell as the company participated in the 2016 public tender for the construction of a GTL plant where gas will be converted into a liquid fuel (gas to liquid): a mega project worth a possible five billion dollars. The facility will convert Mozambican natural gas into diesel for the purposes of sale in the country and abroad. In 2014 Shell received the go-ahead for a feasibility study for the plant and in 2017 won the public tender which 14 companies participated in. Shell now has permission to build and is currently drawing up plans to this end.

Embassy documents reveal how important the efforts of the Dutch government and embassy were in securing this permit. This started immediately after the discovery of gas in 2011. When Secretary of State for Economic Affairs Henk Bleker and the Mozambican Minister of Trade and Industry met in October 2011, part of the ‘intended result’ was to (translated from Dutch):

‘Profile Shell as a party for gas and LNG development in Mozambique’

Sometimes the Dutch embassy and Shell collaborate closely:

‘Just wanted to share an update with you all on the latest developments in Mozambique concerning Shell and domestic gas. Been an intensive 2 weeks where Shell Mozambique, Shell The Hague, UK high commissioner and my team have been working closely working together.’

This is what the Ambassador Grotenhuis wrote in an email (translated from Dutch) dated 25 November 2015. Incidentally, a month after this email one of the embassy’s staff, ‘political and trade advisor’ Felizberto Mulhovo, started working for Shell.

Development projects

The Netherlands is even prepared to use its development work in Mozambique for Shell’s interests and those of Dutch businesses in general. For instance, in May 2013 the plan developed to have local recipients of Dutch development aid promote Dutch gas companies to the Mozambican national gas sector. This concerns two water companies, the Dutch Vitens Evides International (VEI) and its local partner for a decade now, the Mozambican water utility company FIPAG. Both prove willing ‘to utilise [the Dutch water sector’s reputation] for the pitch NL will make to the gas sector,’ reveals an embassy email (in Dutch).

Other development projects have been used to promote Dutch companies as well. For example, the Netherlands gives aid in the form of ‘capacity building projects’: education and training programs about energy extraction for Mozambican civil servants in the public gas sector.

‘Capacity building projects can be used to strategically position Dutch companies in Mozambique’. Stated a Dutch embassy document from February 2014.

Ultimately, these diplomatic efforts deliver results, Shell reports. When the company wrote the thank you letter to the embassy, the first permit (for a feasibility study) had already been awarded.

‘Thank you once again for your boundless efforts to promote the interests of Dutch companies in Mozambique’, Shell concludes its letter.

Financial support

In Mozambique Shell not only receives diplomatic, but possibly also direct or indirect financial support from the Dutch state using a state provided export credit insurance.

What is an export credit insurance?

Dutch companies can insure their projects abroad using an export credit insurance. The company then pays a premium to the Dutch state. In the event of damages, the Dutch tax payer acts as guarantor. This policy is implemented by Atradius Dutch State Business.

Possibly, as there is no transparency about this. A freedom of information request submitted to the Ministry of Finance for all applications since 2010 for export credit insurance for projects in Mozambique, was only partially answered. The ministry refused to provide a crucial file containing about 5,000 documents, namely all those concerning two requests by contractors for the benefit of ‘a Dutch oil company’, because these requests are still being processed. These likely pertain to Shell itself or one of its suppliers. Wiert Wiertsema of Both ENDS, who is a specialist on export credit insurances, explained to us: “Shell almost never takes out an export credit insurance in its own name, more often than not it concerns one for a Shell supplier. Think, for example, of Van Oord, Boskalis, Wittenveen & Bos and others.”

The Ministry of Finance only wants to state that the two requests concern port and offshore activities. The ministry says the large number of documents can be explained by the fact that the contractor has not only submitted a request for an export credit insurance, but also for a Project Financieringstransactie [project funding transaction]. ‘This often concerns large-scale, very complex transactions with long risk horizons, often much larger than an ordinary export credit insurance in scope.’ Shell’s facility is only expected to start in 2026 and so has the aforementioned ‘long risk horizon’.

Billion dollar fraud run through the Netherlands

Lawyer Alda Salomao understands that donor countries have a ‘dilemma’ and have to weigh up development objectives and economic interests. “This balance is often hard to achieve,” says Salomao. However, in recent years we have seen how national governments have prioritised their national economic interests. “Sometimes with no regard for the consequences.” The violation of land rights by the emerging gas industry, which she combats with her NGO Centro Terra Viva as described in the previous article for Down to Earth, is a symptom of this.

Another good example of how Dutch development objectives clash with business interests is the billion dollar fraud that Mozambique committed, that partially ran through a state-run fishing company with its offices in the Netherlands and the Dutch state’s response to this.

This corruption scandal came to light in 2016. The Mozambican state-run fishing company Ematum bv, with its offices registered in the Netherlands, played a major role in this. The company was registered by TMF, one of the largest trust offices in the Netherlands, in August 2013 and was situated along the so-called Zuidas in Amsterdam, a popular, up-market location for international companies. The trust office itself, at the time run by Jan Reint de Vos van Steenwijk, is Ematum bv’s board, as shown by the extract from the Dutch chamber of commerce.

In 2013, the Zuidas based Ematum bv entered into an 850 million dollar loan through Credit Suisse and the Russian VTB Bank for the purchase of French tuna fishing vessels. However, the boats only cost 100 million dollars. The rest proves to have been used to purchase army materials and patrol boats, after it was funneled through to the Mozambican Ministry of Defence (see box). The business plan for the boats’ purchase also contained extremely unrealistic turnover expectations: of the expected tuna turnover of 18 million dollars in 2016 only 450,000 dollars was actually earned.

Export credit insurance for patrol boats

As was the case for the information about export credit insurances of ‘a Dutch oil company’, the Ministry of Finance also refused to release documents about the export credit insurance application of ‘a ship builder and a bank’ in the Netherlands for the delivery of patrol boats to the Mozambican government. The ministry only wishes to state that a guarantee for this project was rescinded in the meantime due to worsening economic conditions. However, the project has not been stopped. ‘It is as yet unsure whether the project will go ahead and whether the export contract will be granted. If this happens after all and the situation in Mozambique has improved in the meantime, the expectation is that a new application will be submitted by the exporter involved,’ so stated the ministry. Due to the Ministry of Finance’s closed-lipped stance we cannot be 100 percent certain whether the application for the delivery of the patrol boats was linked to the abovementioned million dollar fraud. However, the similarities are, to say the least, worrying. We hope to force the government to provide more clarity with regard to this matter by taking them to court.

The affair turns out to be part of a billion dollar fraud orchestrated by the Mozambican government in cooperation with British branches of Credit Suisse and the Russian VTB Bank. This boils down to the Mozambican government, alongside the shady Ematum loan of 850 million dollars, entering into another 1.4 billion dollar loan through two state-owned companies for which it stood as guarantor. However, the government failed to inform the Mozambican parliament (and the international donor community) in direct contravention of Mozambican law. This was ‘clearly’ done to hide corruption, responded IMF director Christine Lagarde angrily when she found out from The Wall Street Journal. Well over half the 2.25 billion dollars can no longer be traced, a research report by auditor Kroll commissioned by the IMF later revealed. It is possible that much of this missing sum ended up in the hands of high-level Frelimo civil servants, writes journalist and Mozambique expert Joseph Hanlon.

The fraud tumbled the Mozambican government into debt crisis: the business plans proved to be just hot air and the Mozambican currency collapsed making the loans in dollars unaffordable in 2016. Mozambique had a raft of demands imposed on it by the IMF – including demands for increased transparency about the affair and the cuts that followed – and saw the international donor community postponing part of its aid to the Mozambican budget, until the demands had been met.

Minister Ploumen partially postponed her annual aid – the 30 million euro budget was cut by approximately 10 million euros – and demanded ‘confidence inspiring’ measures ‘to ensure this never happens again’, so said Ploumen. ‘There can be no business as usual’, she wrote in her letter (translated from Dutch) to the lower house of parliament.

Self-reflection

These harsh words are window-dressing, while self-reflection is lacking, says journalist Joseph Hanlon, who has been writing about Mozambique for 40 years. ‘Where is the Dutch government’s recognition that we, Credit Suisse and the European regulatory institutions, etc. are also responsible? No one is saying that!’, Hanlon complains. After all, the fraudulent financial transaction was set-up and encouraged by Credit Suisse, Hanlon emphasised in a recent opinion piece for the Bretton Woods Project, referencing Kroll’s official study about the fraud. And the fraudsters of the Mozambican state-owned fishing company Ematum bv had their registered offices at a Dutch trust office TMF. The latter should have been aware that ‘it was completely impossible for the tuna fishery industry to pay back the loan’, according to Hanlon.

‘If there are criminals, they are over there’, in Mozambique, is how trust office TMF’s spokesman responds to questions concerning the office’s role in the fraud. He compares a trust office to an ATM to explain TMF’s innocence. ‘Someone goes to an ATM, buys a weapon and kills someone with it. Does that make TMF guilty?’

The Dutch state similarly responded in a lukewarm manner to questions of where to lay the blame. Minister of Finance Jeroen Dijsselbloem answered questions in the lower house of parliament about the matter by arguing that it is not his responsibility to judge TMF’s role, but that of De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB). However, the ‘statutory framework for trust offices’ is currently under review as it indeed proves ‘that trust offices insufficiently substantiate their roles as gatekeepers’, Dijsselbloem admitted.

De Nederlandsche Bank wrote to us stating that it will not release information concerning the current investigation into TMF. And the new trust legislation proves to be a ‘sham’ that is easily evaded according to a recent investigation by Investico for Dutch daily and weekly papers Trouw and De Groene Amsterdammer.

Tax treaty

If the Netherlands truly cared about combating corruption in Mozambique, then the following is just as remarkable a move. After the billion dollar fraud came to light, the Netherlands enthusiastically continued its diplomatic lobbying for a bilateral tax treaty with Mozambique. This is what the requested internal documents and emails from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs reveal. However, Dutch tax treaties, officially intended to prevent ‘double taxation’ are infamous for the international (tax)fraud they can facilitate. This is why in 2013, Mongolia tore up its tax treaty with the Dutch government, after tax evasion by a Canadian mining company using its offices in the Netherlands to abuse the treaty.

It turns out the Dutch corporate sector desires this tax treaty, and the Dutch government gives in to that. The treaty ‘makes it more appealing for Dutch companies to invest in or trade with Mozambique,’ states an email to Grotenhuis sent in May 2017 (we do not know who sent this as their details were censored).

‘The Dutch business community (including Shell, Heineken, Heerema, VNO/NCW) has, on multiple occasions, indicated its interest in a tax treaty between Mozambique and the Netherlands.’ (In Dutch)

The Netherlands had already been promoting the treaty for some time. In April 2015, Secretary of State for Finance Eric Wiebes wrote to the Mozambican government inviting them to start negotiations on the tax treaty. When, after a year, it still had not received a response, the Netherlands increased the pressure. The billion dollar fraud that was discovered in the meantime proved to be no incentive to reticence.

On 29 June 2016, only two months after the fraud was uncovered and two days after Minister Dijsselbloem answered parliamentary questions about TMF’s involvement, the Ministry of Finance revived its lobbying for the tax treaty. In an email to Ambassador Grotenhuis the ministry wrote: ‘Until today, we have not received an answer to that letter. Can you inform me wether the Government of Mozambique agrees to start such negotiations, and if so, when and where we could start our discussions.’ That was sent to Mozambique last year. Did Grotenhuis know whether Mozambique still wanted to start negotiations or not and, if so, when and where?

Other emails show that during the same month (June 2016) preparations were being made for President Filipe Nyusi’s state visit to the Netherlands, scheduled for May 2017. The visit was controversial, so hot on the heels of the billion dollar fraud and while an international investigation into the matter was still underway. ‘The Netherlands has now become the first western donor to revive its ties with the Mozambican government’, Dutch daily newspaper NRC wrote. Moreover, Nyusi was the Minister of Defence when the loans were concluded and part of the controversial million dollar loan ended up with his ministry. ‘My main question is: why now?’, investigative journalist and activist Erik Charas asked himself when speaking to NRC.

In any case, the tax treaty was one of the motives.

‘As you may be aware, the importance of a tax treaty with Mozambique to the Dutch business community has increased in recent [sic]’

states a Ministry of Finance email to Ambassador Grotenhuis dated 16 February 2017, (translated from Dutch) a few months before the state visit. 11 days later, Grotenhuis informs the ministry by email that both Shell and the embassy are marshalling their lobbying forces for the tax treaty (translated from Dutch):

‘Shell also has an appointment with [censored]. So pressure will be applied from several sides.’

The emails between the Ministry of Finance and Grotenhuis reveal that the Netherlands would preferably like to sign the tax treaty during the state visit. In the preceding month Grotenhuis received the tax reforms Heineken would like to see introduced in Mozambique by email (once again the sender has been censored).

‘Just to make sure that we are aligned on what we are asking in or negotiations with the government’,

states the email to Grotenhuis.

It is conspicuous that the ambassador has doubts about her cooperation with Shell and Heineken’s legitimacy.

‘Both Shell and Heineken have invited me to be present during their bilateral events with the president’, Grotenhuis wrote in an email (in Dutch) to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs dated 8 May 2017.‘I would like to consult as to whether you perceive any attendant risks to doing so? To me it seems a logical part of our cooperation, but I would love to hear your view on the matter.’

In the Netherlands there is also cooperation with Shell and Heineken surrounding the state visit. For Shell a 90-minute dinner was planned with President Nyusi for the first day of the visit. Heineken was granted a 30-minute conversation on Day 3.

However, Mozambique was not convinced.

‘It will be an LOI [letter of intent], not the treaty itself’, Grotenhuis wrote on 8 May 2017 to the Ministry of Finance. The intention to conclude a tax treaty has at least been achieved, thanks to Shell and the Dutch government’s lobbying.

Tax evasion

The costs and risks of a bilateral tax treaty with the Netherlands for Mozambique are considerable. Not only the Netherlands, but also non-Dutch multinationals in Mozambique could use the tax treaty to evade taxes as was the case in Mongolia. American, Italian and Thai gas multinationals operate in Mozambique, companies that have had subsidiaries registered in the Netherlands for years. Will the Netherlands combat this abuse? “It’s legitimate to doubt that. And I am expressing myself cautiously here”, says tax expert Jan Vleggeert in his office at Leiden University. “So far, the Netherlands has never resisted this.”

Incidentally, the Netherlands recognised the risk of tax evasion, albeit implicitly in a Dutch language embassy document from 2016 concerning the billion dollar fraud and Ematum bv’s role therein:

‘The Netherlands does not have a tax treaty with Mozambique. Tax evasion therefore seems not to have been the reason for Ematum to base itself in the Netherlands.’

One might add: ‘However, we will work hard to make the tax treaty a reality.’

Perfect storm

There is another reason why the tax treaty with Mozambique was problematic for the country at that precise point in time. It was already suffering a crisis and not just because of the billion dollar fraud. ‘A perfect storm’, as the embassy described it in a May 2016 memo in Dutch to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The billion dollar fraud, the resulting debt crisis resulting from the postponement of international aid as well as extreme draught and famine as a result of El Niño coincided that year. The memo also makes reference to the political crisis underway with continuing ‘skirmishes between armed Renamo groups and the government’s army’.

The Mozambican government requires, precisely while it is being buffeted by this ‘perfect storm’, tax income to provide emergency aid, repayment and development. However, tax treaties aim to lower legal taxation rates for companies and prove to shift tax income from developing countries to richer ones, a study from 2016 pointed out. Tax expert Jan Vleggeert, “What you could ask yourself is: ‘what’s in it for Mozambique?’”. He does not agree that the tax treaty will attract investment in Mozambique. “Look, that gas is there. That’s what the companies want. The only thing this treaty does is ensure Mozambique can levy less tax on the profits created there.”

This might help explain Mozambique’s reticence.

Hidden agenda

The Netherlands has a hidden agenda when it comes to Mozambique. As a donor country it offers a helping hand combating poverty and corruption, or so it says. However, like a pragmatic market trader it joins forces with Shell, while land rights are violated around the area the oil company’s future plant is to be situated in. And while the investigation into the billion dollar fraud the Mozambican government orchestrated through the Netherlands is still underway, the latter has seduced Mozambique to sign a treaty that is mainly of interest to multinationals and local oligarchs. For market trader the Netherlands, Shell’s gas profits and Heineken’s beer turnover come first.

The Dutch government obviously chooses to keep matters under wraps concerning its relationships with Shell and other companies in Mozambique. This suggests there is something to hide. For instance, is Shell receiving financial support using a public export credit insurance and who else is receiving one? Which talking points did Shell submit for the meeting between Prime Minister Mark Rutte and President Nyusi? What did the DNB answer to the queries from the Ministries of Finance and Foreign Affairs concerning their investigation into the role of Dutch trust office TMF in the billion dollar fraud? These are important questions that remain unanswered because many documents and emails have been heavily censored or not handed over at all after requests using the freedom of information act.

Mozambique’s citizens are also sick of the secrecy. “They come here, mark things and don’t provide any information,” says an inhabitant of Quitunde, the area the gas was discovered in, concerning their experiences with Shell and other gas multinationals. “We have been ignored and shown no respect.” Mozambique’s citizens want transparency and a say in matters. “Give us time to come together and discuss the matter with everyone.”

This article was written by Bas van Beek, Alexander Beunder, Jilles Mast and Marianna Takou of the Platform Authentieke Journalistiek as commissioned by Down to Earth Magazine in cooperation with Follow the Money. This publication came about with the support of Both ENDS and the Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten: the authors are responsible for the contents.

Browse the documents yourself

As you are used to from us, we want to give Down to Earth readers the opportunity to browse the documents that were released. We have collated all the documents to this end and have organised them using the online analysis tool Documentcloud. This offers full OCR support which makes the texts from the FOIA-released documents searchable and allows copying. Furthermore, Documentcloud enables readers to annotate, label and mark documents for their own research. These documents are largely in Dutch.

Click here for the documents from the administrative body you are interested in:

• The Ministry of Foreign Affairs

• The Ministry of Finance

• The Ministry of Justice and Security

• The Public Prosecution Service

• De Nederlandsche Bank did not honour our request as it does not wish to share documents concerning its investigation into trust office TMF.

We have sorted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs documents by date by modifying their titles. The oldest document is numbered 2011_001. You can sort the documents on Documentcloud by clicking sort in the menu and subsequently choosing sort by name.

All the documents are searchable. You can quickly create an overview of all the documents that mention a particular subject using keywords. If you first pre-sort the documents according to date, you can quickly and easily create timelines for subjects you are interested in.

You can also download the documents. Select the document then click publish then choose download original pdf.

Responses from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Shell to this article.

We asked both the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Shell to respond to the content of the above article and a number of concrete questions. Below we have published their responses in full:

Shell’s response

‘Mozambique’s government organised a public tendering process for its national gas projects. This tender was competitive and transparent. In total 14 offers were submitted. In January 2017 the government selected three projects including Shell’s Afungi GTL and electricity project. GTL (gas to liquids) is a technology for turning natural gas into high-end liquid products such as fuels.

In June 2017 Shell signed an agreement with Mozambique’s government to confirm the tender’s results. Although the project is still in its infancy and Shell has not arrived at a definitive investment decision, ‘Afungi GTL and Power’ can make an important contribution to the government’s development priorities. Mozambique does not wish to solely benefit from the export of liquid natural gas (LNG), but also wishes to diversify the use of gas to produce fuels, fertilizers and electricity in Mozambique for use at home and abroad. Shell’s intended project can play an important role in this.

Communities

As stated above, the project is still in its infancy. Shell has not selected a location for the project yet and has therefore not concluded any resettlement agreements either. No one is working for Shell in Northern Mozambique at the moment, nor does the company own property there. Shell did – in 2017 – negotiate for temporary access to certain communities’ land in order to carry out soil studies. This was done to collect data for a possible future location for the project. The land owners were compensated to this end. This was Shell’s only activity in this area.

In general, Shell understands that resettlement can lead to fear or concern for the communities involved. This is why we always try to prevent relocation. If the latter becomes unavoidable, we cooperate closely with the communities to help them relocate and to main their standard of living and livelihoods. When we work with local communities we always apply international ethics and standards including the International Finance Corporation Environmental and Social Standards as well as our own ethics and standards

The interests of the Dutch business community in Mozambique

The Dutch embassy in Mozambique looks after the interests of the Dutch government and Dutch companies in Mozambique. Shell appreciates the role the Dutch embassy plays in promoting trade in Mozambique as well as how the embassy reinforces the relationship between Mozambique and the Netherlands.

All Shell’s projects have to be competitive and sustainable before we invest in them. This depends on a large number of factors including taxes. In general Shell supports treaties that reduce the risk of, for example, double taxation for the same capital in two separate countries. For further information on the tax treaty we refer to the Dutch and Mozambican governments. Furthermore, Shell has not applied for any export credit guarantees or insurances from the Dutch government with regard to its commercial activities in Mozambique.

The Ministry of Foreign Affair’s response

The Netherlands always strives for a good balance between aid and trade in its foreign policy. It also does so in Mozambique. There the Netherlands supports sustainable and inclusive growth in three fields.

• Firstly with programmes in the fields of water, healthcare and food security. This concerns clean drinking water, combating HIV/AIDS, improving agriculture and reinforcing land rights.

• The second area of Dutch support concerns programmes promoting transparency and accountability. This allows Mozambique to acquire the capacity to provide improved transparency to its own population. This programme is implemented in, among other places, the north of Mozambique where major gas reserves have been discovered.

• Thirdly economic diplomacy is very important to the Netherlands. We support Dutch companies who wish to do business in Mozambique and we support programmes to improve the local investment climate and private sector.

All three fields reinforce one another and are implemented in an integrated manner as much as possible. The Dutch embassy in Mozambique has properly shaped this balanced approach to aid and trade.

The Dutch government has – in recent years – tried to conclude a bilateral tax treaty with Mozambique. What is the principal motivation for this?

The Netherlands has an extensive network of treaties and continually negotiates with other countries concerning (new) tax treaties. The Ministry of Finance regularly publishes news announcing intended negotiations concerning tax treaties. The countries that negotiations are currently underway with are listed in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ quarterly overview.

The Netherlands wishes to contribute to improved taxation in developing countries precisely because this is a crucial element for sustainable growth and the promotion of self-reliance. Concluding as tax treaty is part of this. The aims behind this are to:

(1) prevent companies or citizens from facing double taxation or from avoiding taxation,

(2) create the greatest possible legal certainty for taxpayers,

(3) reduce the administrative burden, and

(4) provide the basis for mutual support between tax bookkeeping systems. A tax treaty thereby helps improve the economic ties between the countries involved and reinforces administrative collaboration. After all, tax treaties and investment protection agreements offer the legal certainty entrepreneurs and civilians seek when considering investing in developing countries.

Is it not detrimental to Mozambique’s development to lobby for a tax treaty i.e. basically lower taxes for Shell and Heineken, while the country is undergoing a debt crisis and tax income is of vital importance?

Tax treaties are concluded between countries so both may benefit. As indicated in the first answer, a tax treaty can help make investments come about in a developing country.

This is why it is incorrect to assume loss of tax income purely on the basis of a possible lowering of the rate for withholding tax on the basis of the existing cash flows. Reduction of withholding tax often leads to the prevention of double taxation and can therefore contribute to an increase in investment and consequently labour opportunities, profits and – ultimately – also higher income from profit taxation and withholding tax in a country.

Furthermore, the Netherlands takes the exceptional position of developing nations into account as also detailed in the Notitie Fiscaal Verdragsbeleid [fiscal treaty policy memo] 2011. This states, for example, that the Netherlands – in negotiations with developing countries – is more willing to include a broader definition off the term ‘permanent establishment’ or relatively higher withholding tax.

The investigation into the fraud surrounding Ematum bv. and the role of the Dutch trust office TMF is still underway. Would it not have been better to await the results thereof before further expanding fiscal relations in the shape of a tax treaty?

Tax treaties offer the basis for mutual support between tax administrations. As stated in the Notitie Fiscaal Verdragsbeleid 2011, the Netherlands strives to include items on the exchange of information as well as for support for the collection of taxes in treaties. This improves the treaty partners’ ability to apply anti-abuse stipulations on the basis of the information obtained and to combat tax avoidance and evasion.

Can the Dutch government guarantee that a bilateral tax treaty between the Netherlands and Mozambique will not be used for tax evasion by Dutch and non-Dutch companies commercially active in Mozambique? If so, using which tools?

When negotiating tax treaties a great deal of attention is paid to the subject of tax evasion. After all, it represents a serious problem for developing countries as it has a relatively severe impact on these countries’ weak government finances. This is why, in 2014, the Netherlands proposed introducing anti-abuse clauses into the bilateral tax treaties to 23 developing countries. Furthermore, the Netherlands participates in the Multilateral Tool to include the anti-abuse clauses developed by the BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) project in current treaties. These anti-abuse clauses are also part of Dutch treaty policy for yet to be concluded treaties. This offers treaty partners, including developing countries, effective tools for combating tax evasion and helps prevent the extensive network of Dutch tax treaties being abused. Naturally, attention will also be paid to the above in negotiations with Mozambique.

Furthermore, one should note that the Netherlands as well as other donors work to develop technical cooperation with developing countries with regard to taxation. The Netherlands directly or indirectly through multilateral institutions contributes to capacity building for tax authorities and ministries of finance in developing countries including the provision of consultancy to improve developing countries’ knowledge of tax treaties and anti-abuse clauses.

Can the Netherlands guarantee that no land rights are violated in areas as a direct or indirect consequence of Shell’s commercial activities in the country? And, if so, how?

The Netherlands cannot guarantee that no land rights are violated by companies abroad. However, the Dutch cabinet expects Dutch companies to adhere to the OECD guidelines for multinationals and actively addresses companies to this end.

The Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation annually actively enters into dialogue concerning land rights with multinationals, NGOs and other stakeholders. For instance, attention was paid to the situation in Northern Mozambique in particular during the so-called LANDdialoog [land dialogue] in 2016.

The Netherlands has also supported the improvement of land registration in Mozambique for years with the Dutch Kadaster [land register] playing an important advisory role. This takes place at national, provincial and city levels.

Would the Netherlands be willing to stop its cooperation with / diplomatic support for Shell if land rights had been violated as a direct or indirect consequence of Shell’s commercial activities in the country?

There are no indications that Shell violates land rights in Mozambique.

Any zegt

The Dutch Government is owned by the large companies like Shell, Unielever, Heineken, just to name three global companies. Why does these companies stay in the Netherlands. Simply, the own the government so they can do whatever they like. And the high taxes in the Netherlands are just a small price to pay for the gigantic amount of profits these criminals can take. The Dutch government is sick to its bone and the Dutch people are the dumbest on Earth, or the smartest Shell should say. Why do they not have a conscience?

Tayla Hassan zegt

I believe this article was set with positive and educational intentions, which is highly appreciated. However, i must critic the framing created of this country through its title. Referring to Mozambique as “dirt poor”, contradicts the positive intentions you may have set for this article. It creates a dangerous narrative for the people of this country. This is A narrative that continues to plague, developing country’s like Mozambique. As a citizen of this country, i feel highly offended by the narrative this title creates. I believe the author of this article is informed enough to know the dangers of misuse of language, therefore this is an unacceptable detrimental mistake, this is a narrative that has been historically used through colonialism and post colonialism by so called developed countries. I hope to see better as i am greatly disappointed.