Hundreds of Mozambicans died last month as a result of tropical cyclones and the flooding that followed. Decent coastal protection and drainage is entirely lacking. In 2012, the Netherlands designed a master plan for the coastal city of Beira that was fully on trend for new style development cooperation: aid through trade. Can you really leave coastal protection up to market forces?

Cyclone Kenneth hit the northern province of Cabo Delgado in Mozambique ‘like a bulldozer’ on 25 April 2019. Six weeks before, cyclone Idai had destroyed the port city of Beira. Most of the cyclone’s victims died along Mozambique’s coast: some 598 in total. According to the latest count Cyclone Kenneth killed 43 people.

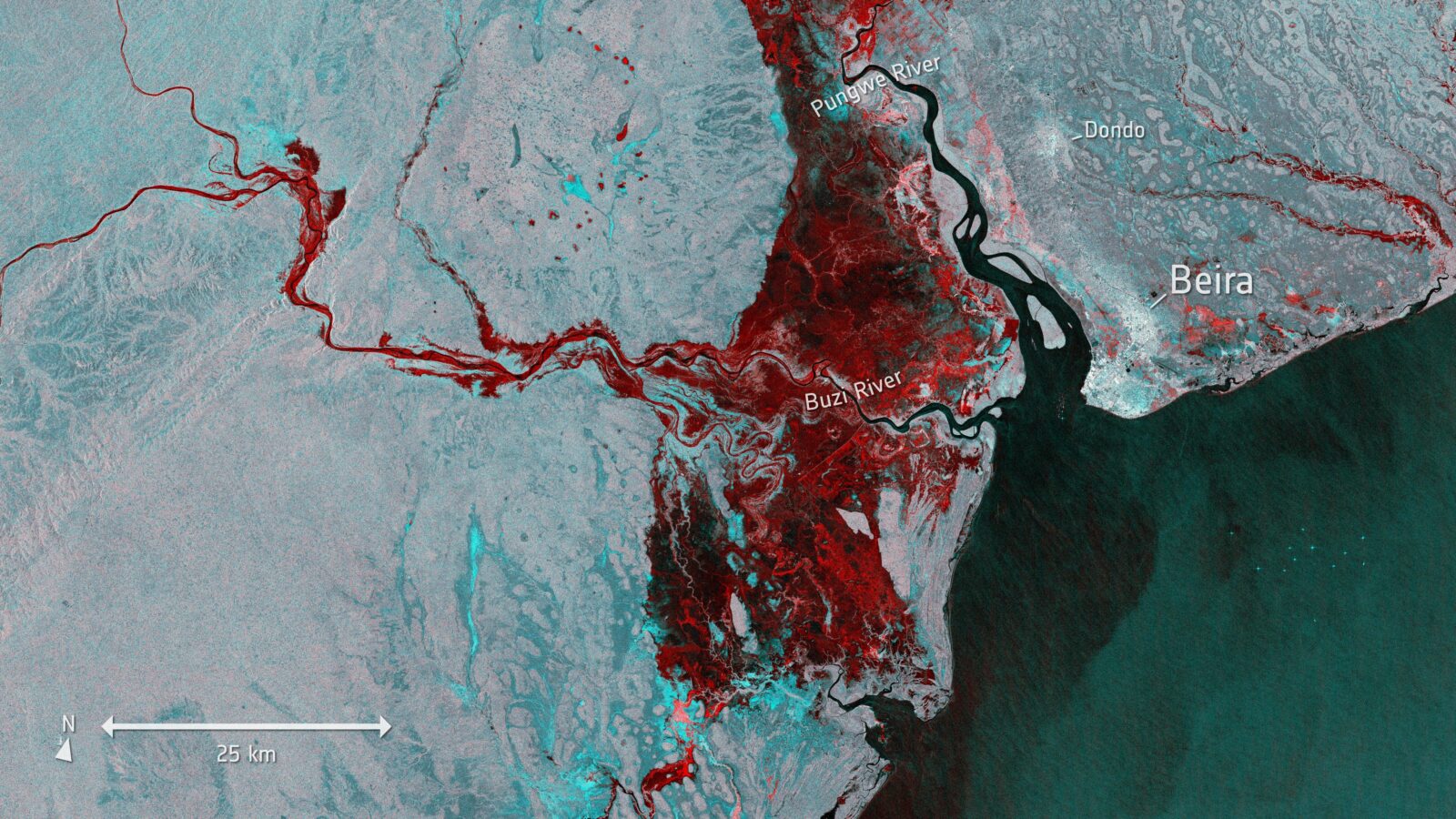

A major part of Beira was flooded after heavy rainfall and a storm surge some 6 metres high. 112,000 homes were damaged or destroyed. To make matters worse, the disaster hit right before harvest time. Thousands of hectares of crops grown by farmers in and around Beira – the city is partly agrarian – were lost.

The cyclones brutally revealed the underlying problem: coastal protection and water discharge are pretty poor in Mozambique and particularly around flood-prone Beira. The city is situated at the swampy mouth of the Pungwe River and forms a ‘bathtub’ that traps water after heavy rain or flooding. Beira has flooded and subsequently suffered a cholera outbreak almost every year since the city’s founding at the close of the 19th century.

Protecting poor Mozambicans from flooding was not a priority for the Portuguese colonists who were ousted by the leftist Frelimo rebels in 1975. The cement homes the Portuguese inhabited were relatively safely situated on higher ground in the dunes, while Mozambicans relied on agricultural activities in the lower lying areas. The independent Frelimo regime also didn’t prioritise Beira’s urban development much. It fought a civil war against the anti-communist Renamo until 1994. Beira was an opposition stronghold full of Renamo rebels.

By now, the western donor community (countries and institutions) has been sponsoring and advising Mozambique – the world’s fifth poorest country in the world – for some 25 years. Beira in particular is known for its close ties with donor countries including the Netherlands. Why were no dikes built to protect the city’s poorest against nature’s extremes during the past quarter century?

Opportunities for the private sector

Modern development aid sets aside a bigger role for the business community. In short: aid should serve developmental goals, but it’s okay for businesses to make a profit. It was on the basis of this principle that the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs examined what it could do for the port of Beira. This general vision was communicated to the Dutch ambassador in Mozambique by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The internal document states that: ‘No large-scale development aid projects will be developed for coastal protection and climate adaptation in Beira, however the Dutch business community will be provided with advice’. ‘You should pay considerable attention to opportunities for the Dutch private sector,’ it adds.

One year on, after public tendering, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs commissioned knowledge institute Deltares and the Witteveen en Bos firm of engineers to develop a proper master plan to make Beira more resilient against climate change, cyclones and flooding risks. This led to the genesis of the ‘Beira Masterplan 2035’ designed with input from a coalition of public and private parties.

In a six-minute video Deltares explains all the ambitious elements the plan consists of. Coastal protection and drainage systems for surplus water should reduce flooding risks. Homes will be built at a safer elevation by topping up a piece of land, all of this to be achieved through a ‘Land Development Company’. A new access road to the port will also be built. All by attracting private investors to fund construction albeit with some support from the Ministry of Development Cooperation to stimulate the investment climate. The idea being, an internal document from the Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland [the Netherlands Enterprise Agency] from 2016 notes, to have the master plan provide ‘multiple opportunities for the Dutch business community’.

Six years down the line and many of the master plan’s elements are still waiting for funding, explains the person responsible Peter Letitre of the Deltares knowledge institute. ‘It’s taking longer than I’d hoped,’ he admits on the phone. Some elements have been implemented such as drainage projects funded by the World Bank that ‘worked well’ during Cyclone Idai, but many ambitions listed in the plan have remained unfulfilled. ‘We hope things will start moving forward thanks to the cyclones.’

Letitre lists a number of local impedances. For instance, a major corruption scandal involving the Frelimo regime came to light in 2016 that damaged Mozambique’s credit worthiness. The still tense relationship between Beira, controlled by the Mozambique Democratic Movement (MDM) opposition party and the central Frelimo regime doesn’t help either.

Aid as long as it generates income

Some elements of the plan seem hard to privately fund as it is anyway. Coastal protection as a common good for example only costs money, never leading to direct income. ‘This is why, as far as coastal protection is concerned, not much has actually been done yet,’ recognises Letitre. After all, the plan examined ‘potential income generating activities as well as measures aimed at funding coastal protection,’ according to Letitre. Coastal protection itself ‘limits damage, but does not generate income’.

At an investment conference held in Beira last June, Letitre assisted the council and the Dutch government in seeking out funding for the master plan, but saw little interest in investing in coastal protection. The World Bank, the largest, government-funded development bank, stated it did not have the funds to this end. According to Letitre tens of millions would be required to fund the coastal protection measures and drainage needed.

That the master plan solely focuses on income generating activities is precisely the problem a 2016 Utrecht University study by Professor Annelies Zoomers and researchers Kei Otsuki and Murtah Shannon posits. Practically speaking the master plan is a collection of business plans for Dutch and foreign investors,’ states the study. According to the researchers this explains why so little attention has been paid to the plan’s social consequences. For instance, the new access road to the port cuts right through an area inhabited by subsistence farmers and the plan presents ‘no vision whatsoever for these farmers who will have to leave their land to make way for the new road’.

Is infrastructure construction in Beira prioritised over social development? A civil servant involved in the Beira master plan, water advisor Maarten Gischler of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, wondered this too and out loud as can be read in the minutes of a conference at the University of Amsterdam in June 2018. Gischler shared his impressions after the investment conference in Beira. ‘In an aid dependent country like Mozambique even a visionary mayor has to adhere to the donors’ infrastructure development agenda,’ Gischler observed.

That the plans had to have ‘income generating potential’ may also explain why the master plan focuses more on better off Mozambicans. At least, that is what the Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving [Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency] (PBL) wrote in a report published last year: ‘On paper the plan is aimed at all the city’s inhabitants both rich and poor. However, the road layout and plot sizes lead us to suspect that ultimately the richer middle classes will be the ones who have the money to build homes in this new plan’.

The Hague’s policy aligns with the international trend

The Beira Masterplan 2035 is therefore, according to those familiar with it, a partially unimplementable plan aimed at ‘income generating’ opportunities for foreign investors and the upper middle class in Mozambique, with perhaps more attention being paid to infrastructural works than to the negative social impact on Beira’s poorest inhabitants. Who is responsible for this? The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in its role as the head of development policy? The Ministry of Economic Affairs because it commissioned the master plan? Deltares and Witteveen & Bos as they designed it? The Dutch embassy in Maputo as it acted as the local fixer?

But things aren’t quite that simple, states Murtah Shannon, the social geographer from Utrecht who co-authored Zoomers’ critical study from 2016. ‘Civil servants are stuck with the development agenda as determined at a national, government level.’ In turn, this national policy is aligned with an international trend, says Shannon, who is currently working on a PhD at Utrecht University studying urban development in Beira.

The best aid is encouraging trade

You should ‘Google ‘post-aid’ and ‘retroliberalism’ sometime,’ says Shannon. These terms describe the global shift in development cooperation, which picked up speed after the 2008 economic crisis. The idea is that aid and trade go well together and that the best aid consists of encouraging trade. Instead of donating goods and services, developing countries are now given more support creating profitable investment opportunities for (foreign) companies.

The Netherlands have also embraced this vision, for instance by combining the portfolio for aid and trade under a single minister in 2012, with Lilianne Ploumen (PvdA) as the first Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation between 2012 and 2017. Ploumen referred to a ‘modernisation agenda’. The trend was applauded, by the business community, for example, but also faced intense criticism, among others from NGOs and critical members of parliament. However, no single responsible party can be indicated, repeats Shannon. ‘It’s shaped by various interests that change continually.’

In this modern form of development cooperation a lot can be achieved over a short period of time as soon as ‘income generating activities’ are concerned. The best example being the Mozal aluminium foundry. The Mozambican government built the foundry at the close of the 1990s with loans from, among others, the World Bank. This was one of the largest investments made in Mozambique since it opened its borders (like so many former socialist states) to foreign investors in exchange for aid funds from donor countries. The factory and the necessary prerequisites such as electricity were rapidly constructed using the well over 2 billion dollars in capital allocated. The joint efforts of international development banks associated with the World Bank ‘led to Mozal’s completion six months ahead of schedule and under budget,’ wrote the World Bank.

This major allocation from funding institutions is easily explained as it concerned an extremely profitable company even for the World Bank. A study conducted by NGOs in 2012 revealed the figures: for every dollar Mozal yields for the Mozambican government, foreign investors earn 21. Australian, Japanese and South African co-owners, but also the World Bank itself, receive most of the profits. In the meantime, Mozal consumes almost half (45%) of the electricity generated in Mozambique, whilst only 12% of Mozambicans have access to electricity, the study indicated.

‘Gas demands rapid infrastructural developments’

After the discovery of an enormous gas field off the Mozambican coast in 2011, the donor community repeatedly recommended that the country invest in the infrastructure needed by the gas industry. ‘Operating the Mozambican gas field demands rapid infrastructural developments such as port facilities and gas processing and transport infrastructure,’ states an internal memo from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs in May 2013. This represents another opportunity for the Dutch business community to make money the memo says. Shell, RoyalHaskoning/DHV, BAM and Boskalis were named as companies interested in participating in the Mozambican gas industry.

The International Monetary Fund encouraged Mozambique to ‘take out more loans,’ a later internal email from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs dating back to October 2013 states. It goes on to say that this was necessary due to the ‘very major investment backlog in infrastructure, agriculture and the development of educated workers’.

In 2013, the Frelimo regime received some 2.25 billion dollars in credit and probably millions in bribes from the Swiss investment bank Credit Suisse. The credit was used to buy boats from Lebanese shipbuilder Privinvest for three nationalised companies that were founded ad hoc. The vessels were to service the future offshore gas industry. This corruption scandal heralded years of fiscal and political crisis. Frelimo is still at odds with the donor countries, the IMF and the investors.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs also already recognised that something was amiss with Mozambican development in the email from October 2013. Some information had been released concerning the loan corruption and this was critically received, so states the email, from the ministry ‘in particular by the donors’.

The email’s author also wonders whether too much is being spent on unnecessary infrastructure. ‘One wonders whether Mozambique really needs all the new ports and railway lines currently planned and whether it wouldn’t be better to upgrade and improve utilisation of the existing infrastructure.’

According to social geographer Shannon, it is also very much the question what the Mozambican people themselves want. It is precisely their voice that often goes unheard, he concludes. For the ‘Beira master plan’ he saw Dutch parties and local administrators draw up plans without much say for the local population. ‘Dependent relationships such as this one do not encourage the wider participation and commitment of the population,’ says Shannon. ‘You really need projects and strategies to achieve that.’

This publication came ab![]() out in conjunction with Follow the Money, and with the support of Both ENDS and the Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten. The authors are responsible for the content.

out in conjunction with Follow the Money, and with the support of Both ENDS and the Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten. The authors are responsible for the content.

Fred zegt

STOM om het Mozambikaanse verhaal niet in het Nederlands te vertalen! En (nogmaals) te publiceren.